16 Sep 2025 “China Plus Wait”: A Risky Bet in Global Sourcing

Written By Francis Bassolino, Managing Partner of Alaris – 5 min read

Pity the sourcing director caught between a board demanding diversification away from China, a finance team obsessed with cost-cutting, and a volatile geopolitical landscape. Solving for this trilemma often leads to a seemingly safe, but ultimately dangerous, strategy known as “China Plus Wait.” It’s like a life hack many in China use to deal with overwhelming pressure – just lie flat and hope the storm passes.

The “China Plus Wait” has its merits and usually arises after a review of the options. For example, companies might conduct pilot sourcing events in places like Mexico, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe. But instead of investing in new supply chains, they use the lower prices and market intelligence from these “frontier markets” as leverage to squeeze existing Chinese suppliers for lower prices.

When Chinese suppliers oblige, buyers often conclude that the cost of switching to a new supply base isn’t worth it. Sourcing teams report back to the board with something along the lines of, “We can push our current Chinese suppliers for better prices, or we can move to Mexico or Vietnam, invest a lot of time and capital, and essentially break even, or even spend more, for the next year or two.”

When pressed for a recommendation, our hypothetical sourcing director shrugs and says: “I don’t know. Vietnam or Mexico might be cheaper in five years, but we will need to invest up front. Who knows what tariffs will look like? Mexico’s dangerous, and Vietnam isn’t as easy as China. I like Eastern Europe, North Africa, and India, but they’re harder to manage and will have long development cycles. And somehow, our Chinese suppliers have matched our target prices again!”

The Fundamental Flaw: Not Knowing Your "Should Cost"

This seemingly logical decision to stick with China, however, reveals a critical misunderstanding of the risks many companies face. First, if a buyer can use a new market price to force an incumbent to lower costs, it proves they were overpaying in the first place. Often, this happens because brand owners don’t truly understand the cost structures of the products and markets they source from. Said differently, they don’t know what the product should cost.

To really know what something should cost, you need to be able to answer: “If I were making this myself, in X location, at Y volumes, what would it cost?” Many marketing-driven companies lack this fundamental understanding because their focus is on consumer demand and what a product can cost in the market, rather than its intrinsic “should cost.”

The Evolution of "Sourcing" and Its Pitfalls

For decades, many US buyers approached Asia with little more than rough sketches and competitor samples. “Sourcing” was essentially presenting loose concepts to suppliers who would then handle the engineering, tooling, and prototyping. Once a viable product emerged with an acceptable gross margin, an order was placed without much analysis of the drivers of cost or aggressive negotiation on cost drivers.

This approach highlights several core risks for many US companies. For example, most buyers are strong on the “front end” – marketing, sales, distribution, and customer relations. They have product concepts but often lack in-house engineering and manufacturing expertise. They simply don’t understand and don’t have the resources to calculate the components of cost from an engineering and manufacturing perspective.

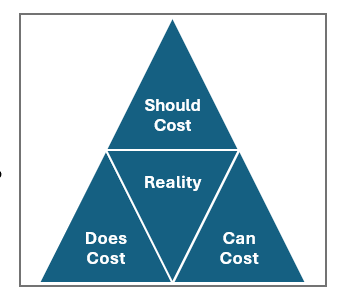

Sourcing is a complex puzzle, where one needs to triangulate on the truth. It starts with a should-cost model, built from the bottom up, component by component. The second leg is shopping the market with a detailed specification to get a market price, or does cost. These two data points allow one to triangulate to an ideal can cost, which confront reality and ultimately settles somewhere in the middle, factoring in all realities of supply, demand and psychology. Many marketing-focused firms are missing a leg or two in this three-legged stool!

Engineering: A High Cost and a Scarce Skill Outside China

An interesting development in global sourcing is the realization that outside of China, engineering is both an upfront cost and a skill which is in short supply. While many suppliers in frontier markets could offer engineering and design services, they are increasingly fed up with “shopping trips” from buyers who never actually place orders. For nearly a decade, consumer goods companies have been exploring many frontier markets without committing to building supply chains there.

The Perils of a Bad Reputation: "Ignore Them, They Never Buy Anything"

An underappreciated problem with simply “shopping” in a frontier market without placing orders is that suppliers lose patience with companies and will blackmark those known to shop without buying. When the next sourcing event comes around, suppliers remember the buyers who never committed. Many buyers underestimate the ramifications of a bad reputation, especially in markets like Vietnam and Mexico, where manufacturing capacity is, and will remain, tight.

Diversification: An Insurance Policy, Not Just a Cost Saver

Another significant flaw in the “China Plus Wait” strategy is that the primary goal of diversifying away from China is security of the supply chain. Cost reduction is a welcome bonus, but it’s not the main objective. Supply diversification is first and foremost an insurance policy, not merely a cost-cutting solution.

While the financial benefits of a new supply chain might take 18-24 months to materialize, the real returns are qualitative. It’s about building a supply chain that can withstand geopolitical storms and is future-proof, capable of handling more scenarios than a single-sourced alternative. In other words, taking action now is the only way to achieve a resilient supply chain in five to ten years, which is roughly how long it takes to develop the necessary infrastructure for a truly robust supply chain.

"You Need Me More Than I Need You": China's Enduring Leverage

US firms have excelled at creating asset-light marketing machines that rely on suppliers for manufacturing and engineering. However, many of these firms face an existential threat if they don’t replicate their China-based capabilities in other frontier markets.

Chinese entrepreneurs are renowned for their adaptability, risk-taking, and tenacity. They’ve responded dynamically to the dramatic shifts of the past decade by automating, improving back-office functions, squeezing their own suppliers, and seeking local government support to weather the storm.

In many markets, China factory gate prices have fallen year-on-year for the past decade. While tariffs have added pressure, China’s countermeasures have closed the gap enough for buyers to reconsider moving away from China. Many conclude, “Vietnam and India aren’t that much cheaper when we factor in switching costs. And who knows what the next US administration will do? Let’s just squeeze China and wait to see what happens.”

Chinese entrepreneurs have explored options like establishing operations in other low-cost locations to avoid tariffs. Some who needed to move to retain customers have done so, while others have exited markets altogether. Critically, many have realized their organizations possess sustainable competitive advantages.

Indeed, many Chinese companies have discovered that US and European buyers often can’t function without them. Even when a US buyer has an engineering team that assisted with developing manufacturing prints, there can be a significant difference between the print and the final product on the market. There are also unwritten rules about “ownership” boundaries. If a firm develops a product with one manufacturer and then shops it to a competitor, it can be viewed as a breach of trust. The entire market might then become wary of developing products with that buyer.

Cracks in the Foundation: The Hidden Costs of Moving

In short, these sourcing exercises in frontier markets have exposed a fundamental structural problem for many US distributors and brand owners which is that they often don’t truly own the drawings, specifications, and tooling. They may own the brand and distribution channel but all that focus on the asset-lite front end means they are capability-lite on the back end! Before they can successfully move to a new region, they’ll need to make significant investments to recreate all these critical elements.

For all these reasons, “China Plus Wait” is akin to the Chinese movement to “lie flat.” It’s a poor strategy, more like an ostrich burying its head in the sand – except ostriches don’t actually do that. When scared, an ostrich lies flat, hoping they will go unnoticed and danger will pass. Unfortunately, leadership in sourcing isn’t a game of hope; it’s a game of probability. And the probability is that a buyer who owns their prints and tooling, and has a diversified supply chain, is far more likely to survive the challenges on the savannah.